Early in the 1960s, Ford of Detroit committed themselves to an all-out campaign to achieve supremacy in motor sport. It was conceived as Ford’s ‘total performance’ marketing package in which the youth market had been identified as the fastest growing sector of demand. The object was to beat the rest of the world, Ferrari in particular, at Le Mans. Initially they tried, unsuccessfully as it turned out, to take over the Ferrari business. After this foundered, in 1963, they started a sports racing project of their own. The AC Cobra, the Shelby Mustang and numerous other competition cars were all very successful using Ford engines.

The racing sports car programme was established in the UK at first. Eric Broadley was hired to design a new Ford GT with former Aston Martin team chief John Wyer to race it, the whole operation being run by British-born engineer, Roy Lunn, through a new organisation known as Ford Advanced Vehicles, or FAV for short.

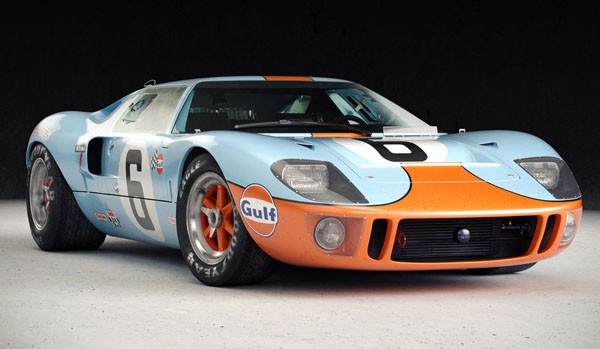

To start the project off Broadley wanted a lightweight monocoque construction, while Lunn – ever mindful of the way things were done in Detroit – demanded a hefty steel structure. Finally Broadley eased himself out to go his own way with the instantly successful Lola T70 sports racer, leaving Lunn to wrestle with a heavyweight flop called the Ford GT40 because it was only 1016 mm high. But it looked sensational and the publicity men back in Detroit hailed it as a world-beater before it had even been road tested. This made the shock even greater when all three GT40s failed to finish at Le Mans in 1964, soundly beaten by Ferraris.

Whilst the cars were very fast in a straight line, there were aerodynamic and transmission problems. In 1965 much of the race and development work was transferred to Shelby America domiciled in California. Here the Mark ll GTs were developed with 7.0-litre V8s, from the Galaxie sedan, installed in place of the original 4.7-litre models but the second Le Mans effort also proved a failure.

Although enraged by their failure at Le Mans, the Americans were learning fast and redesigned the Mark II into a far lighter and more sophisticated J-car. Unfortunately not all the lessons had been learned and it still had a homely two-speed automatic transmission and did not run well in testing. So eight 7.0-litre Mark IIs and five 4.7-litre GT40s lined up with three front-line Ferraris at Le Mans in 1966. Three Mark IIs survived the hard-fought contest for Henry Ford to flag them in 1-2-3 on ‘the best day of his life’.

Meanwhile, enough GT40s had been produced for the model to be homologated for GT racing as Ferrari fought back to humble Ford by taking first three places on Ford’s home ground at Daytona early in 1967. Ford responded by making the J-car a racing reality as the Mark IV with cleaned-up bodywork. This became the first car to exceed 322km/h on the Mulsanne straight at Le Mans, as one of 11 Fords survived to win again.

At this point Ford decided to pull out of motor racing leaving their racing manager, John Wyer, to carry on with the homologated GT40s. They again won the Le Mans and also the World Sports Car championship in 1968, before John Wyer also gave up the Fords, and moved on to manage a Porsche 917 team with quite outstanding success.